Jin

JinYo! I’m Jin!

Look, if you want to understand the heart and soul of Japan—and I mean the real stuff, not just the tourist pamphlets—you have to understand this Kanji.

It’s not just a character; it’s a lifestyle. It’s the reason Japanese society functions the way it does. It’s the “Secret Sauce” of the culture.

Today, we are diving deep into 【和】 (Wa).

This little guy shows up everywhere. It’s in the name of the current era (Reiwa). It’s in the food you drool over (Washoku). It’s probably in the name of your favorite anime protagonist.

Buckle up, because we’re about to decode the most important symbol in the Japanese language.

Data Box (Quick Stats)

Here is the cheat sheet for your flashcards. Memorize this!

- JLPT Level: N3 (Intermediate, but used constantly)

- Onyomi (Sounds): Wa (わ),O(お)、Ka(か)

- Kunyomi (Native Meanings): Yawa-ragu (やわらぐ),Yawa-rageru (やわらげる) ,Nago-mu (なごむ),Nago-yaka(なごやか),na-gu(なぐ),a-eru(あえる)

- Main Meanings: Harmony, Peace, Style, “The Sum” (in math), To Soften.

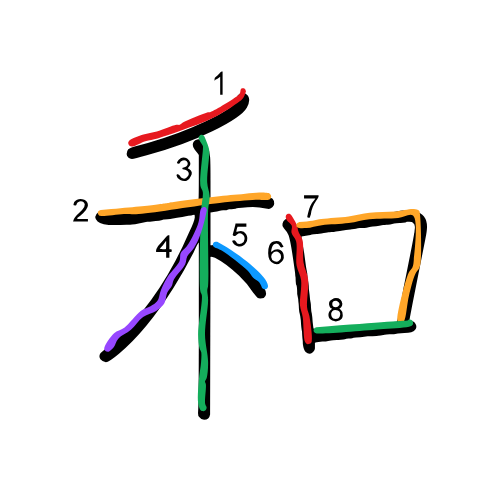

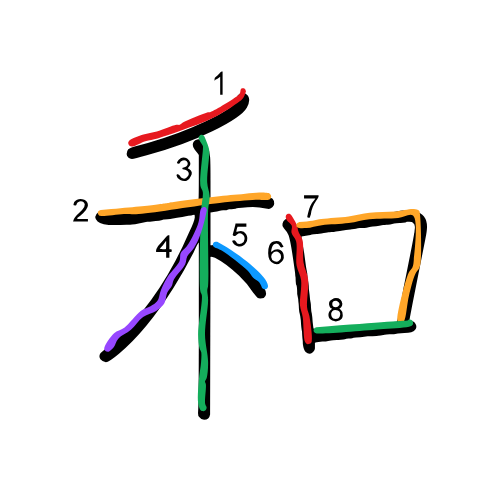

- Stroke Count: 8 Strokes

Introduction

Okay, real talk for a second. Why am I obsessing over this specific Kanji?

Because 【和】 (Wa) isn’t just a word for “Peace.” We have another word for that (Heiwa). No, Wa is something deeper. It’s about blending together. It’s about the vibe being right.

When you walk into a Japanese room and feel instantly calm? That’s Wa. When a team in a sports anime works perfectly together without speaking? That’s Wa.

It is the character that Japan chose to represent itself. When you see “Wa,” read it as “Japan.” That’s how integral this concept is. It’s soft, it’s cool, and honestly? It’s legendary.

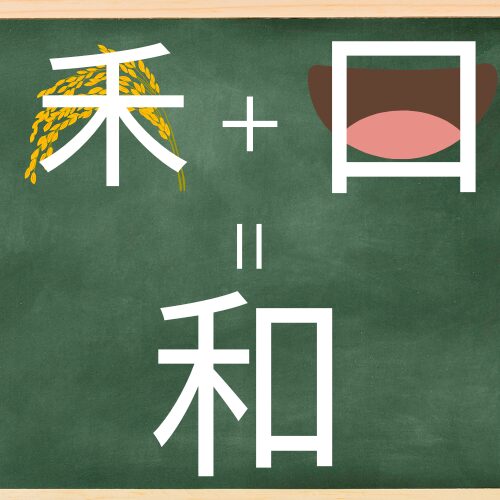

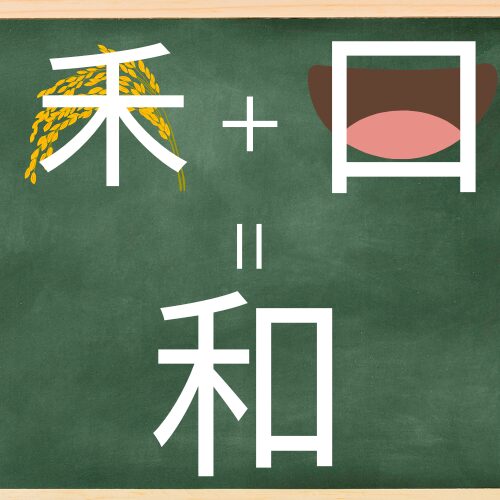

Visual Etymology (The Origin Story)

Let’s break this character down so you never forget it. Imagine we are sitting around a campfire 2,000 years ago.

【和】 is made of two parts:

- Left Side: 禾 (Grain / Rice plant)

- This looks like a little tree with a drooping top, right? That’s a rice stalk heavy with grain.

- Right Side: 口 (Mouth)

- A simple box representing a mouth.

Put them together:

When everyone has Rice (禾) to put in their Mouths (口), there is no fighting. Everyone is fed. Everyone is happy.

That is Harmony.

Isn’t that beautiful? It’s not about rules or laws; it’s about basic human needs being met so we can all chill out together. It’s a visual representation of “sharing a meal.”

Culture & Background (The “Vibe”)

In the West, we often value standing out. “Be unique! Be the main character!”

In Japan, Wa is the counter-culture to that. It’s the spirit of “reading the room” (Kuuki wo yomu). It represents the group over the individual. It’s why Japanese trains are so quiet and clean—because everyone is maintaining the Wa.

But it’s also the word for “Japanese Style.”

- Wa-shoku: Japanese Food.

- Wa-shitsu: Japanese Room (Tatami mats).

- Wa-fuku: Japanese Clothes (Kimono).

This Kanji basically screams: “This is who we are.” It has a spiritual, soft, yet incredibly resilient vibe. Like bamboo—it bends, it harmonizes with the wind, but it doesn’t break.

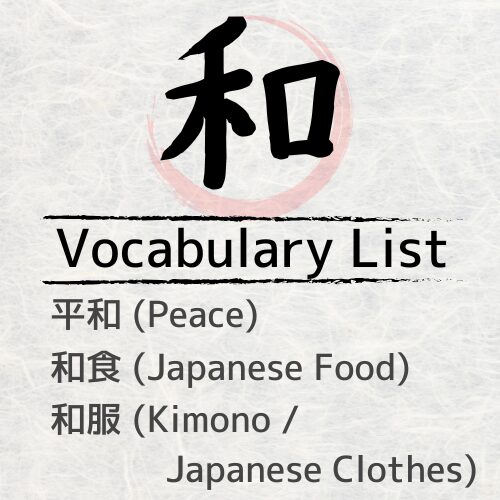

Vocabulary List (20 Words)

Time to level up your vocab. I’ve split these into “Survival Tools” and “Cool Stuff.”

Category A: Basic & Useful (Daily Life)

| Kanji | Reading | Meaning |

| 平和 | Heiwa | Peace (The general concept) |

| 和食 | Washoku | Japanese Food |

| 和服 | Wafuku | Japanese Clothing (Kimono) |

| 和室 | Washitsu | Japanese-style room |

| 調和 | Chouwa | Harmony / Balance (Crucial word!) |

| 和らぐ | Yawaragu | To soften / To calm down |

| 和やか | Nagoyaka | Mild / Peaceful / Genial |

| 英和 | Eiwa | English-Japanese (Dictionary) |

| 中和 | Chuuwa | Neutralize (Chemistry or conflict) |

| 和風 | Wafuu | Japanese-style |

Category B: Cool & Idioms (Anime/Tattoo Worthy)

| Kanji | Reading | Meaning |

| 大和 | Yamato | Ancient Japan / The Spirit of Japan |

| 日和 | Hiyori | Ideal weather / Perfect Day |

| 和魂洋才 | Wakon-Yosai | Japanese Spirit, Western Learning (Badass historical slogan) |

| 緩和 | Kanwa | Relief / Relaxation / Mitigation |

| 温和 | Onwa | Gentle / Mild (personality) |

| 親和性 | Shinwasei | Affinity / Compatibility (Great for tech/chemistry) |

| 不協和音 | Fukyouwaon | Dissonance (The lack of harmony – cool song title word) |

| 和気藹々 | Waki-aiai | Harmonious and happy (Idiom for a good vibe) |

| 令和 | Reiwa | The Current Era (Beautiful Harmony) |

| 和解 | Wakai | Reconciliation (Making up after a fight) |

In Anime & Manga (Otaku Time!)

Okay, my fellow geeks, let’s see where Wa shows up in the worlds we love.

1. Kirito (Sword Art Online)

Did you know Kirito’s real name is Kazuto (和人)?

- The Kanji: Wa (和) + Person (人).

- The Meaning: “Person of Harmony” or “Peacemaker.”

- Why it fits: Despite being a dual-wielding powerhouse who solos bosses, Kirito’s ultimate goal is usually to stop the fighting and protect his friends. He is the bridge between the virtual world and reality. His name reflects a desire for a peaceful existence, even if he’s stuck in a death game.

2. The “Wano” Country (One Piece)

Okay, Oda-sensei writes this as ワノ国 (Wano Kuni) in Katakana mostly, but the “Wa” is absolutely a reference to 和.

- The Meaning: “The Land of Harmony” (Irony alert!).

- The Vibe: Wano is literally Feudal Japan. Samurais, Ninja, isolationism. It represents the Yamato spirit. The entire arc is a battle to restore the true “Harmony” (peace/freedom) to a land that has been corrupted.

3. Captain Yamato (Naruto Shippuden)

His codename is Yamato (ヤマト). While usually written in Kana or 大和, the name Yamato is the ultimate reading of Wa.

- The Vibe: Remember his Wood Release techniques? He creates houses, he suppresses the Nine-Tails’ chakra. His entire role is Control, Balance, and Harmony. He keeps the chaotic Team 7 from killing each other. He is the literal embodiment of “Wa”—keeping the peace among crazy ninjas.

FAQ

Q: Can I use 【和】 for a tattoo?

A: Absolutely. It is one of the safest and most respectable Kanji tattoos you can get. It’s elegant, not aggressive, and deeply meaningful. It shows you appreciate balance.

Q: Is “Wa” the same as the “Peace” sign?

A: Not exactly. “Peace” sign is usually associated with Heiwa (平和). Wa (和) on its own is more about “softness” and “blending in.” It’s less about “No War” and more about “Good Vibes.”

Q: Why do Japanese people say “Yamato” for Japan?

A: “Yamato” was the name of the ancient court that united Japan. The Kanji 大和 (Great Harmony) was applied to the sound “Yamato.” It’s the poetic, old-school name for the country.

Designer’s Note: The Art of Balance

I designed this piece to capture the true essence of “Wa” through contrast. I paired a bold, grounding brush-style for the Kanji with delicate, monochrome cherry blossoms.

Unlike typical pink sakura art, this uses a “Sumi-e” (ink wash painting) aesthetic. It’s quiet, mature, and timeless. I purposely stripped away the bright colors so the meaning of the word—Harmony—could take center stage.

Interior Tip: Because this print is strictly black, white, and grey, it is incredibly versatile.

It fits any color scheme. I highly recommend placing this in a home office or a study. The strong character helps you focus, while the falling petals remind you to stay calm under pressure.

Get This Art

Do you need a little more Zen in your life? (Don’t we all?)

If you want to bring this energy into your gaming room, your office, or just have it as a constant reminder to stay chill when things get chaotic, check out the digital download in my shop.

Print it, frame it, and let the Wa flow through you!

https://www.etsy.com/listing/4352602583/japanese-kanji-art-print-wa-peace

https://www.etsy.com/listing/4361357267/set-of-3-sakura-kanji-art-harmony-love

https://www.etsy.com/listing/4406729591/japanese-cherry-blossom-kanji-art-set

コメント