It’s not just about loneliness.

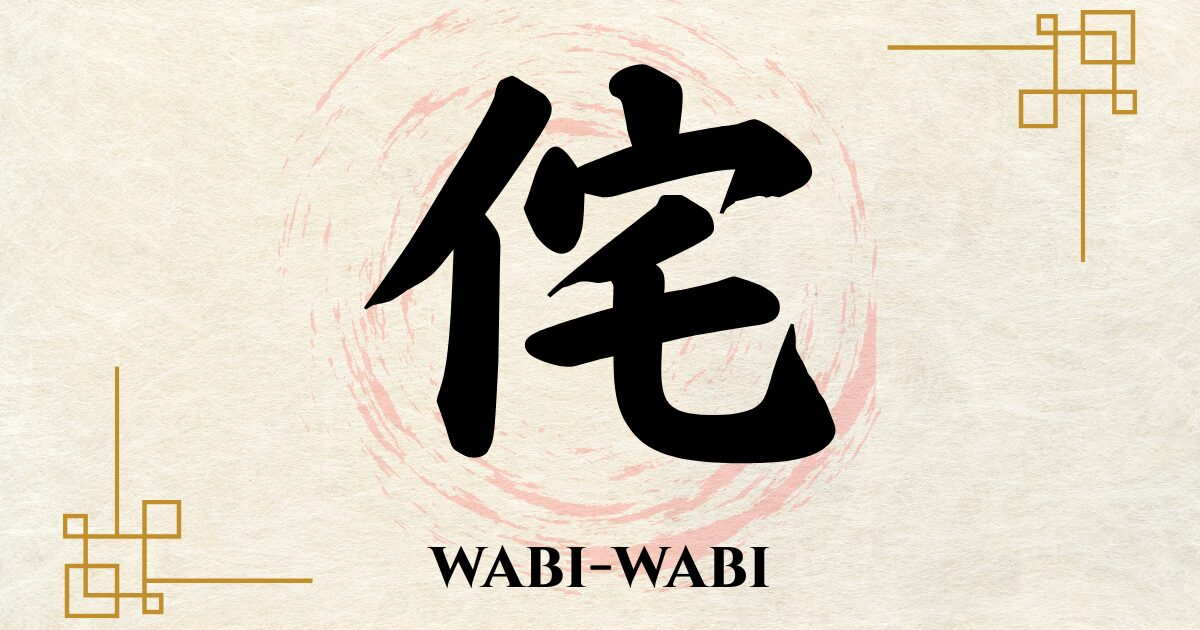

When people see the kanji character “侘 (Wabi)”, they may think it simply means “loneliness” or “poverty.”

But the story of Wabi goes much deeper.

Its essence is not about lacking or suffering, but about finding quiet beauty, depth, and contentment in simplicity and imperfection.

Over centuries, this single character grew to embody not only modesty, but also tranquility, humility, and the refined spirit of Japanese aesthetics.

The Origins of the Character

The kanji 侘 is made of two parts:

- 亻 (ninben) — meaning “person”

- 宅 (taku) — meaning “house, dwelling”

Originally, the image suggests “a person in their home, living simply and modestly.”

In early usage, 侘 carried a nuance of being unsatisfied or feeling a lack.

However, over time its meaning transformed into the positive aesthetic of quiet strength, finding beauty in simplicity, and accepting life as it is.

“Wabi” in Japanese Aesthetics

The true significance of 侘 (Wabi) lies in its role within Japanese aesthetics, especially in the philosophy of 侘寂 (Wabi-sabi).

- Beauty in Imperfection: Cracked pottery repaired with gold (kintsugi) or a weathered wooden gate is not seen as ruined, but as enriched with history and character.

- Simplicity over Extravagance: A single wildflower in a plain vase may carry more elegance than an ornate arrangement.

- Tranquility in Poverty: Rather than luxury, Wabi finds serenity in modest surroundings, where the absence of excess reveals the essence of life.

A Historical Anchor: The Tea Ceremony

Wabi became a guiding principle in the Japanese Tea Ceremony (茶の湯, chanoyu), especially under the influence of Sen no Rikyū in the 16th century.

He transformed tea gatherings from displays of wealth into profound spiritual experiences rooted in simplicity.

Every detail—the rustic tea hut, the imperfect tea bowl, the seasonal flower—embodied the essence of Wabi.

Through this, 侘 was elevated from a negative connotation to one of the highest cultural ideals.

How to Read “侘” (Wabi)

On-yomi (Sino-Japanese reading):

- ta (タ) — the Sino-Japanese reading, rarely used alone but important in compounds.

Kun-yomi (native Japanese readings):

- wabi(る) / wabiru (わびる) — to feel apologetic; to be dejected; to express regret.

- hoko(ru) / hokoru (ほこる) — to be proud; to boast.

Note: The kun-yomi wabiru evolved into the cultural concept of “Wabi,” especially in 侘寂 (wabi-sabi).

While originally carrying a nuance of apology or sorrow, it came to express tranquility and the refined beauty of imperfection.

This reading (hokoru) is less related to the aesthetic sense of Wabi, but exists in classical usage.」

Closing

When you bring the kanji 侘 (Wabi) into your home, you are welcoming more than just “loneliness.”

You are inviting a spirit of quiet elegance, simplicity, and the acceptance of imperfection that lies at the heart of Japanese aesthetics.

In the spirit of Wabi, beauty is not in what is perfect, but in what is imperfect, incomplete, and transient—just like life itself.

コメント